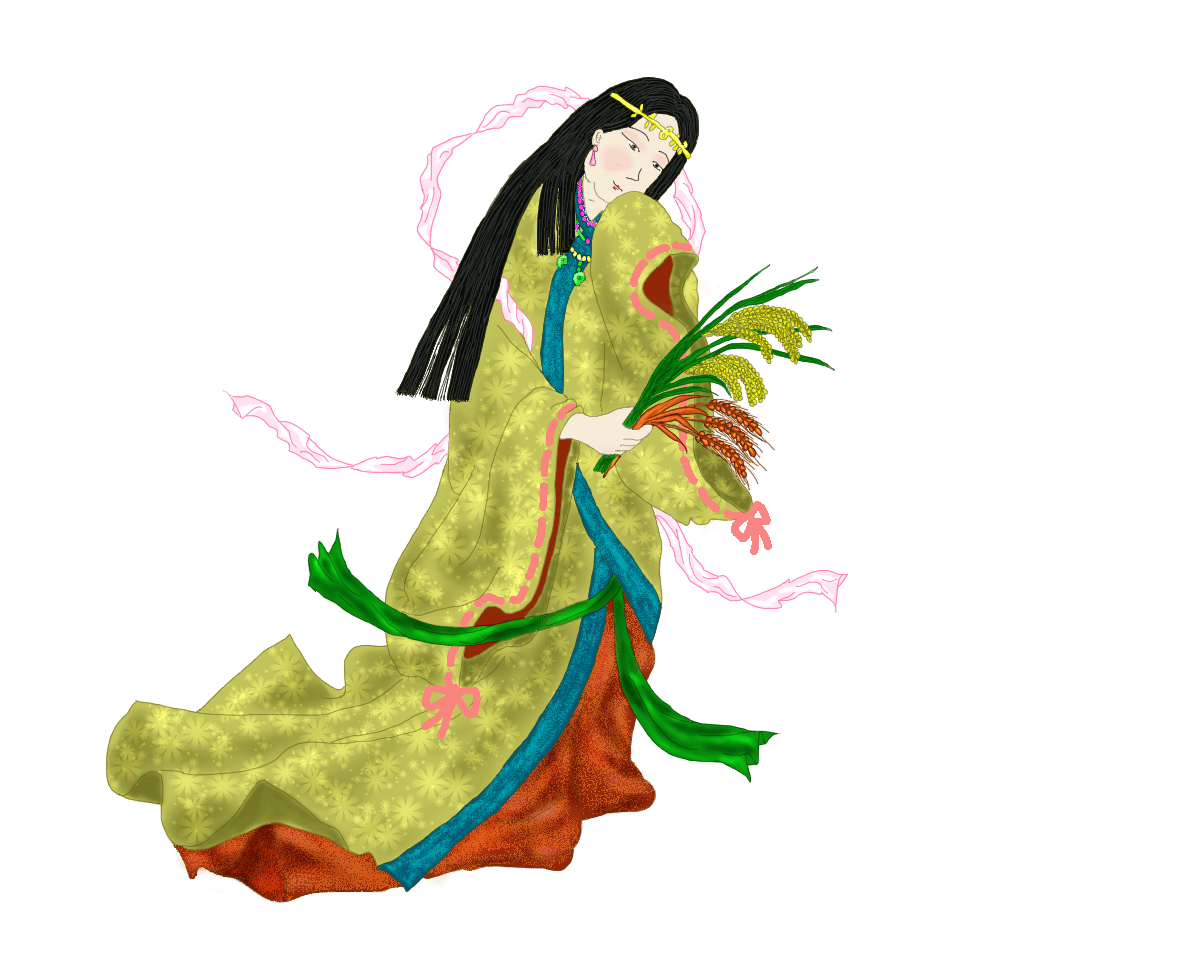

In my previous writings about the deities of Japan and the skies of Tokushima, I briefly mentioned encounters with Japanese mythology’s gods and goddesses. This time, I’d like to reflect on my encounter with the god of food, Ogetsuhime.

When researching food and agricultural deities, various gods and goddesses emerge. Ogetsuhime, being the child of Izanami and Izanagi, has captured my attention. While the goddess Toyukebime, enshrined at the outer shrine of Ise Jingu, appears as a deity related to food, there are also legends of her as the heavenly robe maiden. From my experience of witnessing a rainbow-colored celestial maiden in 2013, I see a connection between Toyukebime and Ogetsuhime.

Since I was young, I’ve been a food enthusiast, often called being “greedy.” I couldn’t wait until dinner after returning home from school, often lingering beside my mother as she cooked. Eventually, I learned to cook myself, mastering basic dishes by the time I was in elementary school. Cooking was enjoyable. On family birthdays, I often baked cakes and prepared full-course meals. While my culinary experiments occasionally failed, I learned from them. Discovering that methods I had devised were later found in textbooks or basics of Japanese cuisine was personally satisfying.

Mixing ingredients to create something new is fascinating. Cooking engages all five senses—touch, sight, smell, sound, and taste—making it enjoyable. Therefore, I experiment with everything in the kitchen, making miso and soy sauce from scratch, even crafting acorn miso from the plentiful acorns falling in my yard during autumn. I’ve also learned to make natto from airborne fermentation bacteria.

As you may know, there’s a close relationship between food and health. After nearly dying from severe postpartum bleeding, I suffered from poor health for years. I experienced firsthand how changing my diet affected my well-being. When asked why I became a dentist, I once replied, “Because I loved eating.” This answer was met with a wry smile. Food enters our bodies first, chewed by our teeth, and flows throughout our bodies. Whole-body health starts with the mouth. I learned this after experiencing poor health.

Now, let’s return to mythology. In Japanese mythology, Ogetsuhime appears in a tale where she’s cooking food, and Susanoonomikoto peeks and sees her extracting various foods from her nose, mouth, and buttocks. Outraged by this act, Susanoonomikoto kills Ogetsuhime. From her slain body, rice plants grow from her eyes, beans from her nose, and wheat from her buttocks. This myth explains why Ogetsuhime is associated with grains, sericulture, agriculture, and food.

[The Food Deity Ogetsuhime and the Jomon Culture]

Ogetsuhime is also a local deity in Awa Province, present-day Tokushima. Awa, which means “millet” and is mentioned in Japanese mythology, gives rise to the deity’s name. Ogetsuhime is enshrined at Oasama Shrine in Godoyama, Kamiyama-cho, Tokushima Prefecture. The deity is associated with the bountiful crops grown here, particularly the “Oasa” variety known for its abundant harvests. As millet was a staple crop in the Jomon period before the introduction of rice cultivation, Ogetsuhime is considered a deity of slash-and-burn agriculture, the precursor to rice farming in Japan.

The Jomon period, lasting for over 10,000 years, preceded the short Yayoi period, which lasted for about 600 to 1000 years. Recently, there has been a growing recognition of the greatness of the Jomon period due to its advanced civilization aligned with the laws of nature. The period was at the forefront of what we now call a “sustainable society,” which lasted for over 10,000 years without signs of conflict or war. Learning from the Jomon period may help us address modern crises. Ogetsuhime, as a deity of pre-rice agriculture, is a fascinating figure in this regard.

Ogetsuhime’s myth, where she dies and gives birth to grains and silkworms, symbolizes the natural cycle of death and rebirth. It represents the cycle of life. Similar stories of death and rebirth, where various crops emerge from a slain body’s parts, are found across the Pacific Rim, Southeast Asia, Central and South America, and Africa. This reflects the universal concept of death, rebirth, and the eternal existence of life, not only for grains but for all living beings in the natural world. Saying “Itadakimasu” before eating in Japan expresses gratitude for receiving the lives of other beings as food. It also expresses gratitude to everyone involved in bringing the meal to the table.

Indeed, the meal before us isn’t just fish or meat but also vegetables and fruits, which, like us, breathe and take in water to live—life itself. Eating is a moment in the cycle of life. Food teaches us the importance of gratitude for life. Learning mythology reminds us of what our ancestors have cherished and passed down for generations.